This is going to be a rather long post. I’ll preface it with some demographic trends among my generation, then tie that in with my situation and how I got here. From there, we’ll see where it goes.

I was born in the early 80s, which technically makes me a Millennial, though it doesn’t always feel that way. Millennials get maligned for a lot of things, which is pretty typical of all generations as they rise, from what I can tell. Civilization is constantly under attack by barbarians, most of whom we call “children,” which is really just another way of saying this:

Every generation reinvents the world.

— Joe Vasicek (@ldssfwriter) May 10, 2018

So how is my generation currently reinventing the world?

Thus far, not very well. The Great Recession hit us just as we were coming of age, and it shows. We were much more likely to move back in with our parents than previous generations. We’re putting off marriage and home ownership, some because we’re more focused on our careers, others because we just can’t seem to launch.

At the same time, not all of this is bad. In spite of the fact that most of us were never taught home economics or personal finance in high school (thanks, Baby Boomers, for all the participation trophies), we are rapidly learning more responsibility than our parents. Where six out of ten Americans would have to beg, borrow, or steal to cover a $500 emergency expense, nearly half of us Millennials have $15,000 or more in savings.

And yet, the problems we’ve inherited are truly daunting. Our national debt is $21 trillion and counting, and without facing a recession, war, or other emergency event, our deficit is still set to exceed $1 trillion per year for the forseeable future. Just this month, we learned that Medicare is set to run out of money in eight years, and Social Security is not far behind that. And don’t even get me started on the house of cards that is our national pension system.

Up until the 60s, previous generations saved and invested so that their children could be better off than they were. The Baby Boomers not only squandered this wealth, but they stole their children’s and grandchildren’s inheritance as well. History teaches us that there will be a terrible price to be paid for all of this. Our parents have proven themselves incapable of doing anything other than kicking the can down the road to oblivion.

That probably sounds more bitter than I intended it to be. Unfortunately, it’s the truth. Our parents just don’t understand the world that we’re living in. We’ve come of age in a world with far less opportunity than they did.

I had a conversation with my mother last year that demonstrates this. My mother likes to make cascarones for special events, like Easter or birthdays. To make them, however, you need a hollowed-out eggshell, which requires removing the yolk and whites in a very particular way. If you’re accumulating shells through normal consumption, it can get to be rather tedious.

One day, I came into the kitchen to find my mother blowing out eggshells and dumping the whites and yolks down the sink. She’d bought a whole bunch of them for 35¢ a dozen, and decided to just make the cascarones all at once instead of accumulating the shells over time. When I saw this, I was horrified.

“How could you waste all those eggs?” I asked.

“It’s not a waste,” she said. “They were 35¢ a dozen.”

“Yes, but we could have eaten them. That’s perfectly good food you’re dumping down the drain.”

She shrugged, as if it didn’t really matter. But I pressed her a bit further, until I came to a disturbing realization:

My mother has never been as poor as I am.

When I pointed this out to her, her answer was even more disturbing. With anger in her voice, she snapped “that’s because you choose to be poor.”

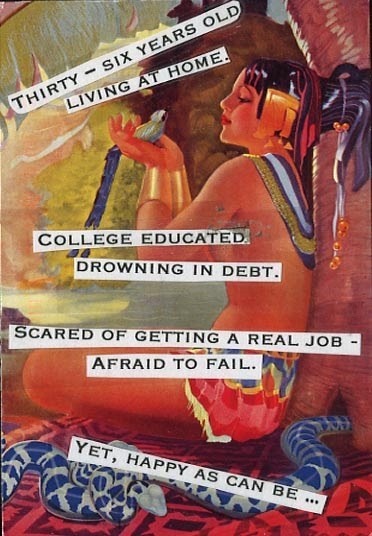

Is that true? Am I, a Millennial, poor because I choose to be poor? Perhaps. I’m not so irresponsible that I won’t own up to my life decisions, which have brought me to this place. But I think there’s this perception in the minds of our parents and grandparents that Millennials are generally like the person who wrote this postsecret above. Drowning in debt, living at home, so afraid to fail that we’ve utterly failed to launch, and yet blissfully oblivious to all of it. Perhaps that’s true for some of us, but not for those who will reinvent the world after our parents are gone.

To be clear, I love my mother and father. I don’t hold any of this against them personally, or anyone else of my parents’ generation (except the politicians who sold our Constitutional birthright, but that’s another rant altogether). Unfortunately, hard truths do not become softer because we choose to ignore them. And hard truth is this:

Hard men make good times.

Good times make soft men.

Soft men make bad times.

Bad times make hard men.

I graduated college in 2010. Through a combination of scholarship money, campus jobs, and (yes) generous parents, I was fortunate enough to graduate without any student debt. At the same time, it was the height of the Great Recession, and jobs were nearly impossible to come by. I can’t tell you how many of my writing friends put their dreams on hold, or abandoned them altogether. Almost all of them.

As a side note, I agree with Mike Rowe that “follow your passion” is bullshit advice. It ranks right up there with “be yourself,” and “you can be anything if you put your mind to it.” Don’t follow your passion. Follow opportunity, and take your passion with you.

But in 2010, I had an opportunity. Without any debt, and without any dependents or other obligations, I decided to pursue a writing career. And unbeknownst to me at the time, the industry was undergoing a revolution that would open the doors to make that possible.

I indie published my first short story, Memoirs of a Snowflake, in March 2011 and never looked back. Since then, I’ve published dozens of novels, novellas, short stories, and other works. It’s been an exhilarating journey. At the same time, it’s been the most difficult struggle of my life. And that is why I must now confront one of my most crippling fears.

Unlike the girl in the postsecret, I am not crippled by the fear of failure. If I were, I would never have published that first story, let alone all the others that followed. Instead, I have a fear of admitting failure, both publicly and to myself. It feels too much like an admission of defeat.

It’s an important distinction to make, though. The Romans admitted failure often and early—it’s how they learned from their defeats, ultimately going on to build one of the most powerful militaries in the ancient world. But they never admitted defeat. Even after Cannae, when Hannibal threatened the republic with utter extinction, the Romans refused to be defeated. And so, while Carthage fell into decline and decadence, the Romans endured until Scipio finally gave them victory at Zama, paving the way for the rise of Western Civilization.

I haven’t had a personal Cannae moment yet, but I do feel like I’ve been fighting a war of attrition. In 2014, the market shifted with the launch of Kindle Unlimited, and I failed to adapt. At that point, I was just on the cusp of going full-time with my writing, though looking back I can see that I didn’t yet have the foundation for a lasting career. Still, to have that dream snatched away when I was just on the verge of catching it, you can understand why I kept plugging along, believing that I was just a month or two from turning things around.

That’s basically what I’ve been doing for the last four years: writing full-time even though the writing doesn’t pay full-time wages. Maybe my mother is right. Maybe I have chosen to be poor.

And yet, while I now believe that I do have the foundation for a lasting career, I need to confront the fact that it may be ten years or more before I achieve it. Should I continue, like so many of my peers, to delay major life decisions until my career reaches that point? Is it worth it to put off marriage, family, and home ownership until my forties or fifties, if that’s what it takes? Or is it time to admit failure so that I can leave this dead end and find another way?

Back in 2010, I had no plan B. It was the Great Recession. I didn’t have a day job because I couldn’t find one—hardly anyone could. And from 2013 to 2014, writing paid well enough that I didn’t need one. Things were looking up, and I was just a couple months away from a sustainable long-term career.

Well, it’s time to admit that that line of thinking has turned out to be a trap. I’m approaching my mid-thirties and I’m still single and poor. I need some kind of long-term backup, because I can’t count on the writing career to take off like I need it to, at least not anytime soon.

So I’ve moved my writing onto a part-time footing. I’m limiting the number of words I write each day, leaving time for other pursuits. And I’m looking for a day job, preferably one that teaches me something useful and pays well enough to make ends meet.

I haven’t been defeated yet, though. Failure is not final until you decide to give up. I have not given up, and will continue to write, even if only on a part-time basis. And when I am making enough to go full-time, I have the foundations in place to do so.

In the meantime, though, I’m not going to put my life on hold for a dream.

I think another issue is that older generations have turned the housing market into something very heavily skewed toward the types of houses that only people at the middle or end of their careers can afford. There are almost no small starter homes being built almost anywhere, so millennials are stuck renting or living at home until they finally the sort of jobs that have high enough salaries to pay for a home. Even the apartment industry mostly just builds nice, expensive apartments because the older generations that control the local governments are very against building cheaper apartments.

But to go back to your main theme, I think our parents were raised in a time when options for careers and housing were plentiful. It was easy to follow some dream of a career path and end up with a nice home shortly after college. Our generation was raised on their hope that opportunities would be even more plentiful. It’s hard for people that have only known a world of plenty to raise kids for a world of scarcity that requires a lot more sacrifice and adaptability.