For the longest time, I thought I was a “discovery writer.” That is to say, I believed there were two kinds of writers—pantsers vs. plotters—and that I was very much a pantser. It was what I was comfortable with. It was what I defaulted to when I sat down to write. It was the style of writing that for me, produced the best books.

Or so I thought.

Ten years later, I come to a realization: my writing process needs work. In order to keep writing at a professional level, I need to produce more books, and to do that, I need to write cleaner first drafts. Discovery writing was great for short stories or novellas, but my novels always seemed to hit a block somewhere in the messy middle. If I want to put out a new book each month, that’s not something I can afford.

Around this time, I read The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. The second habit, “begin with the end in mind,” challenged everything I thought I knew about writing. According to Stephen Covey, everything is created twice: first in the mind, then in reality. To achieve maximum effectiveness in your work, make sure you have a clear plan.

“But wait!” I said. “I’m a pantser—a discovery writer. I don’t do outlines. That’s for plotters.”

And then I thought about it.

What if the whole “pantser vs. plotter” dichotomy is wrong? What if you have to master both skills to really be a masterful writer? Sure, there are plenty of successful writers who never do, but would they be more effective if they did?

What if it’s a bit like talent? People believe that you need talent to be successful, when in reality, talent is just a starting point. A writer who works hard to improve their craft will always overtake a talented writer who doesn’t. And yet, this myth of talent persists, mainly because people can’t see (or don’t want to see) all the hard work that goes alongside it.

This is the conclusion I’ve come to: that when it comes to professional writing, there are no “pantsers” or “plotters.” There are only different forms of outlining. It may be as simple as a one-paragraph sketch, or it may be as complex as a two-hundred page story bible. There are as many outlining methods as there are writers, and many writers tweak their methods with each book in an effort to improve their process.

“Discovery writing” was what came easy to me, but to achieve my full potential, I had to embrace the stuff that was hard. And that meant learning to make an effective outline.

The Old Writing Process

Here’s how I used to write a book:

I’d get a bunch of ideas and do nothing with them. Nothing at all. I told myself I was just letting them stew in the back of my mind, but really it was just an excuse to not do any outlining.

Eventually, the muse would hit me over the head, and an idea would become so compelling that I couldn’t not write about it. At this point, I’d come up with an opening scene and a premise for the rest of the book. I’d also have a vague idea of how the story was going to end, but I wouldn’t pursue it at all, for fear that too much planning would “ruin” it.

All of the other ideas would start to come together, but without an outline to show how they were all connected, I would lose sight of it almost immediately. After writing the first couple of chapters, I soon found myself in the thick of the forest, with only the vaguest idea of where I was going. Soon, I’d lose sight of the forest for the trees. I’d hit a block and try to push my way through, only to find that I was lost.

At this point, I’d set the unfinished WIP aside for a few months, to approach it with “fresh eyes.” It was basically a failed draft. When I felt ready to pick it up again, I would start all over from the beginning, recycling all the stuff that seemed to work and cutting out the stuff that didn’t.

If things went well, I’d push through that block and write the next few chapters… until I came to another block, and had to set it aside again.

If things did not go well, I’d hit the same block only to find that I couldn’t push through it. Something was broken that was fundamental to the story itself. If I was lucky, I’d catch onto that fact soon enough not to lose too much writing time. But more often than not, I’d spent weeks and months agonizing over it, and beating myself up for being a horrible writer.

This would go on for years. My pile of unfinished WIPs grew increasingly larger as I bounced from one failed draft to the next. Usually on the third or fourth attempt, though, I’d push all the way to the ending—not quite the ending I first had in mind, but one that still worked. Kind of sort of.

Then came the revisions.

I’d set the book aside again, usually for a few months. When I was confident I could approach it with “fresh eyes,” I’d pick it up again, only to realize that it suuuuuucked. A little bit angry with myself for writing such a crappy book, I’d go at it with an axe. Characters, subplots, and chapters would all get cut out.

After mauling my WIP to pieces, I’d stitch it back together, usually with the scenes in different order. Then I’d set it aside for a few months again. Rinse and repeat.

Eventually, it would reach a point where it didn’t suck. The ideas would finally come together in some approximation of the way I’d originally envisioned—or would have envisioned, if I’d made the effort beforehand to do so. I’d send it out to my beleagured beta readers (some of whom I’d dragged through multiple drafts), make a few final tweaks, and then start the publication process.

By now, several months would have passed since I’d published anything. If I was lucky, I’d get a couple dozen preorders and sell a few dozen more in the first month. If not, I’d release it to a chorus of crickets.

The New Writing Process

Anything worth creating is worth creating twice.

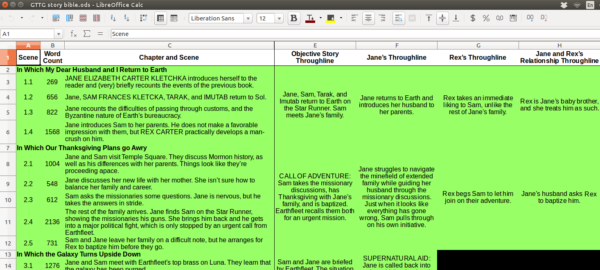

The first creation starts with a rough outline of the plot. According to Dramatica theory, a complete plot has four throughlines:

- The Objective Throughline is the basic overview; the general’s view. It’s what you tell people when they ask “what’s your story about?”

- The Main Character Throughline is the story as experienced by the primary character through whom the readers insert themselves into the story—basically, the character that all the kids fight to be. “I’m Belle!” No, I’m Belle!” “No, you can be Gaston.” “But I don’t want to be Gaston!”

- The Impact Character Throughline is the story as experienced by the foil or counterpoint to the main character, who creates most of the tension that drives the story forward. “Fine, then, you can be the Beast.” “Okay, but next time, I get to be Belle!”

- The Relationship Throughline is like the objective throughline, but focused on just the relationship between the main character and the impact character. As both characters change and grow, the best way to show that is often through the changes in their relationship.

Once I’ve figured out the throughlines, I match them up in a spreadsheet to form chapters. Each chapter breaks down into three or more scenes, which serve to advance the throughlines. The scenes also work together to create a beginning, middle, and end for each chapter.

Once I’ve figured out the throughlines, I match them up in a spreadsheet to form chapters. Each chapter breaks down into three or more scenes, which serve to advance the throughlines. The scenes also work together to create a beginning, middle, and end for each chapter.

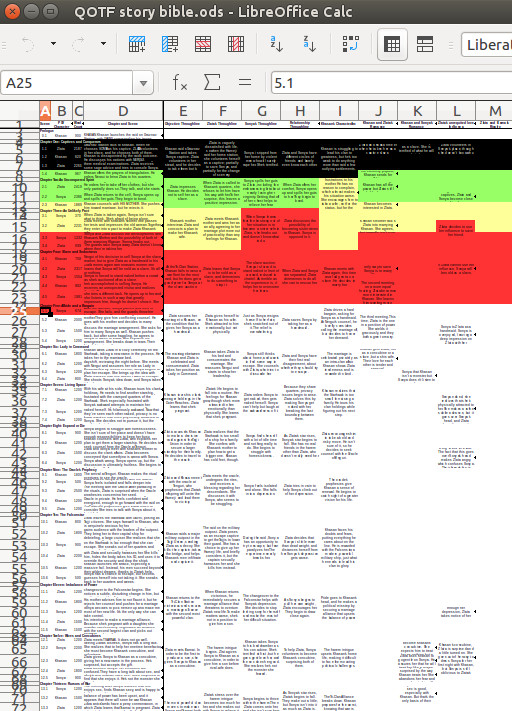

At this point, with the main plot of the book fully outlined, I start to add subplots. These can be romantic, tragic, or just an opportunity for one of the minor characters to shine. I may also add a background storyline with stuff going on behind the scenes that never makes the page, just to keep track of what’s going on.

Where the plot points for the throughlines correspond to whole chapters, the plot points for the subplots correspond to the scene level. A subplot may start or end in the middle of the book, or lay dormant for several chapters. I try to make each scene do double-duty, but add new ones as necessary.

For each of the major characters, I also write up a character sheet. This lists all of the specific details that tend to get mixed up in a rough draft, like hair color, eye color, height, weight, etc. It also gives me a chance to do a deep dive into who this character is and what makes them tick. Besides things like religion, education, occupation level, etc, I also include things like family relations, backstory, strengths and weaknesses, handicaps, etc.

Beyond that, I may draw up a sheet for conflict alignments, or to list all the story tropes that I want to include in the story. It really depends on the book.

Lately, I’ve been experimenting with a process for revising my WIP as I’m drafting it. I keep a sheet for revision notes and color each scene and plot point for which draft phase it’s currently in: red for first draft, yellow for first revision pass, green for second revision pass, and black for final draft.

Lately, I’ve been experimenting with a process for revising my WIP as I’m drafting it. I keep a sheet for revision notes and color each scene and plot point for which draft phase it’s currently in: red for first draft, yellow for first revision pass, green for second revision pass, and black for final draft.

After fixing all the major issues, usually on the first or second pass, I set a goal to cut 10% of the words in the scene. Usually I end up cutting closer to 20%. This improves the quality of the writing and helps to make it much tighter.

I’m still experimenting a lot with my outlining techniques, trying out new things and refining the things I’ve previously tried. A year from now, I’m sure it will look much different. But the two major parts that do work quite well are the plot outline and the character sheets. Everything else builds on top of that.

And the really cool part is that it actually works. From June to August, I started a full-time job, moved twice, and experienced a family emergency, and I still managed to finish a novel through all of that, largely thanks to this outline. No writing blocks. No failed drafts. Just 600 words a day, no matter what else was going on, and by the end of it, I had a publishable novel.

I think this book will help me to write longer books, too. That’s what I’m working on next. If all goes according to plan, Queen of the Falconstar will be my longest book yet—not by very much, but still a good 10k words longer than Bringing Stella Home, which is currently my longest book. The things I’m learning now will help me to write more epic fantasy, like the next two books in the Twelfth Sword Trilogy. That’s the goal at least.

If there’s nothing else I’d like you to take from this post, it’s this: don’t be afraid to try new things. Don’t put yourself into a corner by saying things like “I’m a discover writer,” or “I’m not really an outliner.” Try it! You learn a lot more from your failures than you do from you successes.