So the hero has crossed the threshold of adventure, thwarted the trickster, evaded the vamp, and met with the goddess. He may have lost his mentor and descended into the deepest dungeon, but by calling on the supernatural aid he received at the beginning of the quest, he has passed the final test, found atonement with his father, and come back stronger than he ever was before.

So now that that’s all done, what’s left? Just one thing, really–he has to receive the ultimate boon, or in other words, get the MacGuffin that he came out questing for in the first place.

A MacGuffin is an object whose main (sometimes only) purpose in a story is to motivate the plot. It is usually something that everyone is chasing after, whether it be a ticking time bomb, a briefcase full of money, a priceless artifact, or some sort of superweapon. Basically, it can be almost anything–that’s kind of the point. If you can replace an object with something completely different that serves the exact same plot purpose–for example, a priceless stolen Picasso with a priceless stolen Dead Sea scroll–then it’s a MacGuffin.

Like it or not, MacGuffins are everywhere in fiction. It’s such a prevalent trope, it even has its own Wikipedia page. One of the most famous examples, at least in the Western literary tradition, is the Holy Grail. Another example is the One Ring from Lord of the Rings–it could just as easily be a bracelet, or earring, or any other wearable artifact (though admittedly, if it were a necklace and Gollum had to bite off Frodo’s head, that would change the story quite a bit). The MacGuffin page on tvtropes lists nearly 30 subtropes, from Egg MacGuffin to I’m Dying, Please Take My MacGuffin.

So what does this have to do with the hero’s journey? The last phase of the initiation cycle (basically, all the stuff between the departure and return) is known as the Ultimate Boon. It not only represents the achievement of the hero’s quest, it represents receiving something to bring to the people back home. As Joseph Campbell pointed out:

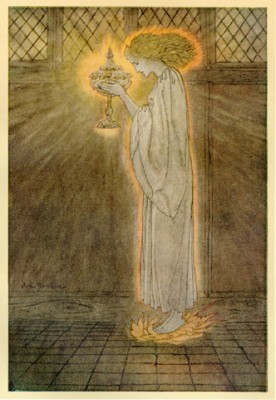

The gods and goddesses then are to be understood as embodiments and custodians of the elixir of Imperishable Being, but not themselves the Ultimate in its primary state. What the hero seeks through his intercourse with them is therefore not finally themselves, but their grace, i.e., the power of their sustaining substance…This is the miraculous energy of the thunderbolts of Zeus, Yahweh, and the Supreme Buddha, the fertility of the rain of Viracocha, the virtue announced by the bell rung in the Mass at the consecration, and the light of the ultimate illumination of the saint and sage. Its guardians dare release it only to the duly proven.

According to Vogler, the hero has to return home with something to benefit himself or the community–otherwise, the whole journey has been a waste of time. Before entering the return phase, then, the hero has to receive the object of his quest.

At this point, it’s worth pointing out that tropes are neither good nor bad. Just because a story revolves around a MacGuffin doesn’t automatically make it cheap or formulaic. Tropes themselves are value neutral–what matters is how you, as the author, use them. Some of the greatest and most inspiring stories of all time make heavy use of MacGuffins.

Because the MacGuffin is a plot-centric trope, when you really understand how it works, you can do some interesting writerly things with it. Michael Moorcock, for example, used this trope to formulate a method for writing a novel in just three days. Would you like to be able to write a novel in three days? Gosh, I’d like to. And before you write that off as formulaic crap, remember, it wasn’t just anyone who came up with this method–it was Michael Moorcock.

In my own work, the best example of this trope would have to be Stella from Bringing Stella Home. As you might have gathered from the title, Stella serves as a MacGuffin for her brother James (specifically, in The President’s Daughter flavor). She does have her own character arc, of course, but as far as James’s storyline is concerned, she could just as well be his mother, or cousin, or <insert kidnapped loved one here>. I did a similar thing in Stars of Blood and Glory, an as-yet-unpublished sequel to Bringing Stella Home, but it should be coming out in January or February of next year so you’ll have a chance to read it then.