If you don’t know anything else about the universe, you should know this: it’s big. Really, really, REALLY big.

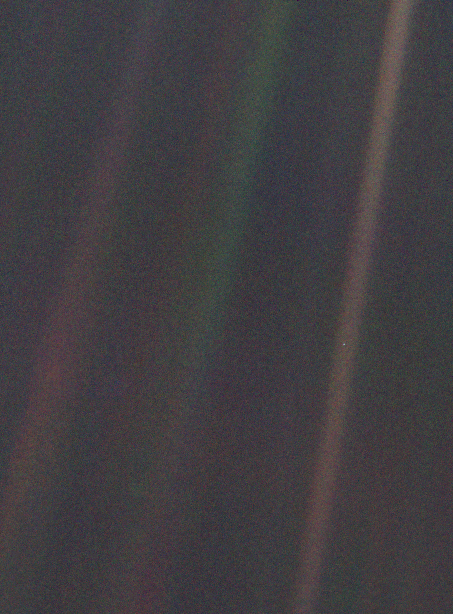

How big, you ask? Well, for starters, take a look at Earth in the picture above. Can you see it? It’s the pale blue dot in the beam of starlight on the right side of the picture. As Carl Sagan so famously put it:

From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest. But for us, it’s different. Consider again that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The picture was taken by the Voyager 1 spacecraft more than a decade ago. At the time, the spacecraft was about 6,000,000,000 kilometers from Earth, or 5.56 light-hours. A light-hour is the distance a particle of light can travel in one hour (assuming it’s traveling through a vacuum). To give you some sense of scale, in one light-second, a particle of light can travel around the circumference of the Earth seven and a half times.

And lest you think that’s actually a distance of any cosmic significance, consider this: the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, is about 4.24 light-years away. That’s more than 6,500 times the distance in the photograph above–and that’s just the closest star!

Our galaxy, the Milky Way, is between 100,000 to 120,000 light-years across. If you were on the other side of the galaxy and had a telescope powerful enough to get a good view of Earth, you would see a gigantic ice sheet over both of the poles with no visible sign of humanity whatosever. The light from all our cities, from our prehistoric ancestors’ campfires, has not yet traveled more than a fraction of the distance across this galactic island universe we call home.

Seriously, the universe is huge. If you don’t believe me, download Celestia and take yourself for a spin. In case you haven’t heard of it, Celestia is basically like Google Earth, except for the universe. Everything is to scale, and there are all sorts of plugins and mods for exoplanets, nebulae, space probes, and other fascinating celestial objects.

I remember what it was like when I first tried out Celestia back in 2010. I was at the Barlow Center for the BYU Washington Seminar program, in the little library just below the dorms. I think it was twilight or something, and I hadn’t yet turned on the lights. The building had a bit of that Northeast feel to it, like something old and rickety (though not as old as some of the buildings up here in New England). I turned off the ambient light option to make it look more realistic, and began to zoom out.

Let me tell you, the chills I got as the Milky Way disappeared to blackness were like nothing I’ve felt ever since. So much space, so much emptiness. It’s insane. The vastness between stars is just mind boggling–absolutely mind-boggling.

I got my first introduction to science fiction when I saw Star Wars IV: A New Hope as a seven year old boy. In the next few years, I think I checked out every single Star Wars novel in our local library’s collection. It wasn’t enough. Whenever I was on an errand with my mom, I tried to pick up a new one. I think they even left some copies of the Young Jedi Knight series under my pillow when I lost my last few baby teeth.

One of those summers, we drove down to Texas for a family vacation. I picked up the second Star Wars book in the Corellian trilogy, written by Roger Allen McBride. It was completely unlike any of the other Star Wars books I’d ever read. In it, Han Solo’s brother leads a terrorist organization in the heart of their home system of Corellia. They hijack an ancient alien artifact and use it to set up a force field that makes it impossible for anyone to enter hyperspace within a couple of light hours from the system sun. The part that blew my mind was that without FTL tech, it would take the good guys years to get to the station with the terrorists.

All of a sudden, the Star Wars universe didn’t seem so small anymore. And it only got crazier. Roger Allen McBride did an excellent job getting across the true vastness of space. At one point, Admiral Ackbar mused on just how puny their wars must seem to the stars, which measure their lifespans in the billions of years. For the ten year old me, it was truly mind boggling.

That was my first taste of science fiction that went one step beyond the typical melodrama of most space opera. And once I had that taste, I couldn’t really stop. As much as I love a good space adventure, real-life astronomy offers just as much of a sense of wonder. When a good author combines the classic tropes of science fiction in a space-based setting that captures the true vastness of this universe we live in, it’s as delicious as chocolate cake–more so, even.

I try to capture a bit of that in my own fiction, though I’m not always sure how much I succeed. In Star Wanderers, the vastness of space is especially significant for the characters because their FTL tech is so rudimentary that it still takes months to travel between stars. All of that time out in the void can really make you feel lonely–or, if you have someone to share it with, it can bring you closer together than almost anything else. It’s the same in Genesis Earth, which is also about a boy and a girl who venture into the vastness alone. The Gaia Nova books lean closer to the action/adventure side of space opera, but the same sensibility is still there.

The best science fiction, in my opinion, both deepens and broadens our relationship with this marvelous place we call the universe. It’s not just a fantastic setting for the sake of a fantastic setting–it’s the universe that we actually live in, or at least a plausible version of it set in a parallel or future reality. The universe is an amazing, beautiful place, and my appreciation for it only grows the more science fiction I read. If I can get that across in my own books, then I know that I’ve done something right.

Human beings really don’t like being small, I don’t think. It’s SO hard for us to even comprehend the vastness of space. But I love your descriptions of your sense of wonder as a child.

Rinelle Grey

Thanks!