This post isn’t just about the third book in the Ender’s Game series–it’s about the genocide of an entire alien race, which is actually a fairly important trope in science fiction.

This post isn’t just about the third book in the Ender’s Game series–it’s about the genocide of an entire alien race, which is actually a fairly important trope in science fiction.

Of all the evils of our modern era, perhaps the most heinous is the systematic extermination of an entire race or ethnicity. These acts of genocide not only cross the moral event horizon, they create specters and villains that live on from generation to generation. Just look at how the Nazis are portrayed in popular culture–even today, they are practically mascots of the ultimate evil.

And for good reason. There really is something evil about the total annihilation of a foreign culture. It’s one of the reasons why terms like “genocide” and “ethnic cleansing” are so controversial, especially in conflicts that are still ongoing–and there are so many unresolved conflicts where the systematic and purposeful annihilation of a race or culture is still happening.

Is wholesale genocide a phenomenon unique to our modern age? Probably not, but modern science has enabled it on a scale that was previously impossible. This became all too clear to us after World War II. Only a generation before, great numbers of people believed that we were on a path of progress that would eventually culminate in world peace. If there was any of that sentiment left, it was shattered with the liberation of Auschwitz and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Suddenly, we realized that systematic mass destruction and genocide were not only possible, they were a modern reality.

It should come as no surprise, then, that science fiction immediately began to explore this issue. From Frankenstein to 1984, science fiction has been full of cautionary tales of science gone wrong, issuing a critical voice of warning. But after 1945, it went much further, exploring the issue in ways that can only be done in a science fictional setting.

Is genocide ever morally justifiable? In our current world, probably not, but what if an alien race was bent on our destruction? If their primary objective was the utter annihilation the human race, and negotiation was impossible? Wouldn’t it be justifiable–perhaps imperative even–to stop such a race by annihilating them first?

This is what is meant by the term “xenocide.” A portmanteau of “xenos,” the Greek word for stranger, and “genocide,” it denotes the complete extermination of an alien race.

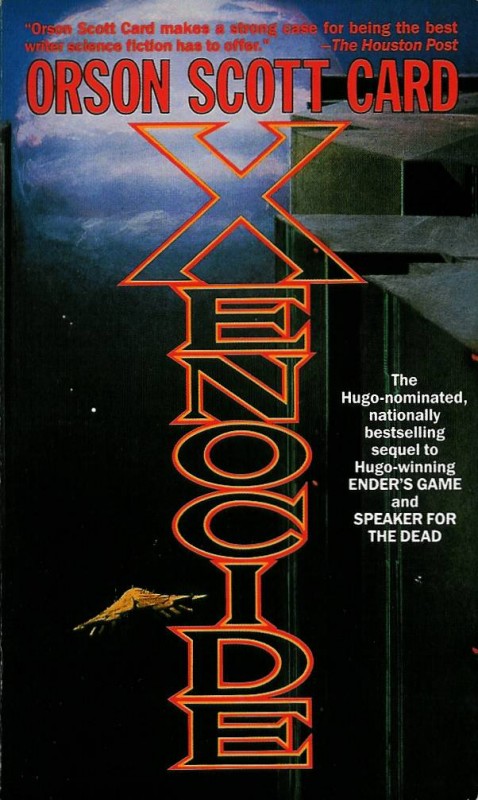

Xenocide forms the core conflict of Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game series (hence the title of the third book) and features in The Forever War by Joe Haldeman. Battlestar Galactica presents an interesting twist, where the cylons debate the ethical questions surrounding the complete annihilation of the humans. And then, of course, there’s all the time travel stories involving Hitler–let’s not even go there.

The interesting thing about xenocide stories is that even though they describe a dilemma that does not currently exist in our modern world, they inevitably come down to issues of Otherness that lie at the very core of the evils of genocide. In order for xenocide to be morally justifiable, you have to know your enemy well enough to know that there’s no possibility of forging any sort of peace with them. And to know them that well, they cease to be quite so alien. It’s one of the major themes in Orson Scott Card’s work–that to defeat an enemy, you have to know them so well that you can’t help but love them.

In our modern world, genocide is only possible when an ethnic group is relegated to the position of Other–when they are made out to be so different and unlike us that we can never possibly relate to or mix with them. They become “sticks” (Germany), “cockroaches” (Rwanda), “animals” and “barbarians” (Israel). That is precisely why it makes us uncomfortable in stories about xenocide–because it turns the well-intentioned saviors of humanity into knights templar, or possibly the very monsters they are trying to destroy.

By positing a situation in which genocide might actually be justifiable, science fiction helps us to understand exactly why it is so reprehensible–and that’s only one of the ways in which the genre can uniquely explore these issues. That’s one of the things I love so much about science fiction: its ability to take things to their extreme logical conclusions, and thus help us to see our own real-world issues in ways that would otherwise be impossible.

Since most of my characters are human, xenocide as such isn’t a major theme in my books, but genocide certainly is. In the Gaia Nova series, the starfaring Hameji look down on the Planetborn as inferior beings and think nothing of enslaving them and slagging entire worlds. That’s how Prince Abaqa from Stars of Blood and Glory sees the universe at first, but by the end of the novel he’s not quite so sure. Stella from Sholpan and Bringing Stella Home also deals with these issues as she comes to realize how it’s possible for the Hameji to hold to such a belief system.

If genocide is one of the ugly skeletons in the closet of this screwed up modern world, then xenocide is science fiction’s way of taking those skeletons out and dignifying them with a proper burial. By wrestling with these issues in stories set on other worlds, we are better able to humanize the Other and prevent these horrors from happening again on our own. In this way and so many others, science fiction helps us to build a better world.

The moral dilemas are often the most interesting to explore. And you’ve done a good job at exploring it here too.

Rinelle Grey

Thanks!